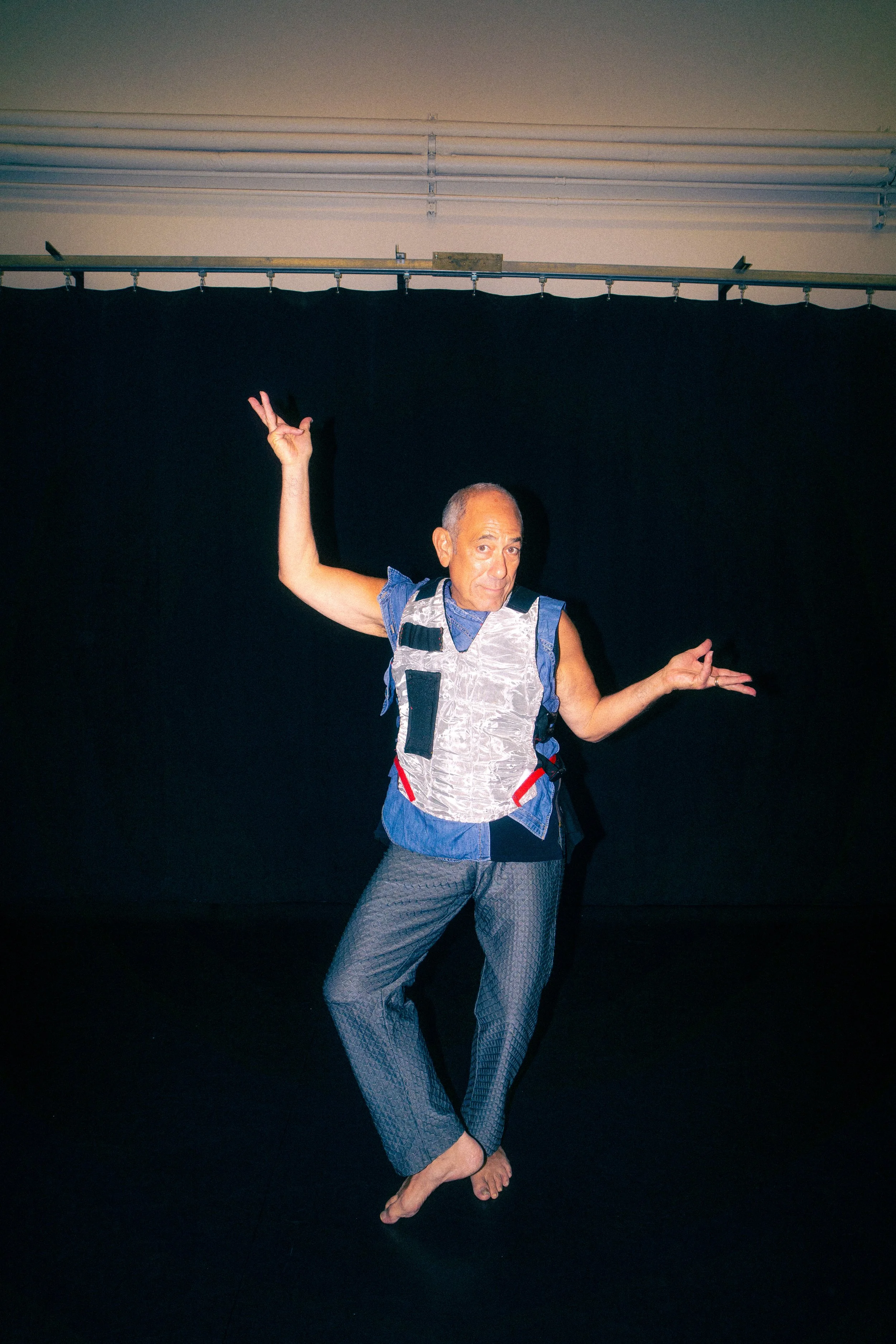

David Dorfman on Movement, Activism, and the Spaces In-Between

For more than four decades, David Dorfman has been shaping the modern-contemporary dance landscape with choreography that refuses to separate movement from meaning. His works—brimming with themes of community, activism, and vulnerability—are as much about human connection as they are about artistry.

Lately, Dorfman’s creative process begins not with a fixed vision, but with words. “I like to use word prompts for individual movement generation,” he explains. “I ask everyone to improvise on their own in a given ‘state’ for a minute or two to words like, what you would have said or the most beautiful thing you’ve never seen. Then, after a number of prompts, I ask all to make a set phrase of choreography out of the highlights or lowlights of their solo explorations. This way the subconscious and unconscious can be active in a low-stakes way, new movements are usually discovered—and the phrases don’t need to have any literal logic, don’t need to make sense—but somehow they have a kinetic, guttural pertinence to the material we want to explore. And then all have solo material that can be utilized on its own or combined with spoken text generation of a similar nature—or of a completely divergent one.”

Sometimes, the prompts are more charged. “Like the other day, when I gave the words surrender, power, care, resist, everyone had to pick one word, quickly write down a story from each of a few recent years that had happened to them, pick one of the stories, and make a dialogue out of that story contextualized—and possibly exaggerated—by a few other prompts like pick a place, a color, a smell, a fantasy costume, set, etc. I randomly split them into duets and they had to combine the two dialogues in some way and utilize movement made up via the above ‘states’ creation model to stage the new event. Sounds complicated—but not really—and it usually yields fantastic surprises and depth about themselves and their past and future worlds.”

Improvisation is a constant. “We do many, many group improvisations where I’ll give a prompt or two that have poetic or prosaic suggestions—time catches you or you are not you—and perhaps some task-oriented score parameters, like someone enters, someone has to exit or one unison stillness. So the company members are delving into content individually and as a community, but also relating to each other as people, on a more quotidian level.”

Collaboration is non-negotiable in his company. “Let me first say that the company members are brilliant, and when we create an evening, it is done together,” he says. “All the movement and partnering and much of the staging is done collaboratively, so only on occasion do I have a super clear idea from start to finish that I bring in to put on the company. Our work usually emerges out of trial and error, hunches, happy accidents, context shifting, and a lot of repetition. All partnering that you see on stage has been created by the dancers, with my direction once a good amount of material has been made. So we try to let go of ownership and go for what best communicates and excites us. I act as the outside eye and director, which I believe takes an ultimate pressure off the performers and welcomes new possibilities and input from all throughout the process. We play a lot, enjoy the time, discover wildly, and we challenge each other—and the overall process.”

That openness extends to technology’s role in dance. In an age of motion capture, AI, and immersive video, Dorfman embraces digital tools—when they have purpose. “I see dance responding in a myriad of ways—we can’t help it—it’s a highly digital world we live in now. For me, the crucial question is: what is the amalgam or intersection of art and technology doing or saying? If technology appears as digital tools to wow folx, or for its own sake, then I’m not as interested. But when technological tools are woven as a means to a newly discovered ‘end,’ then I love it. If technology can bring performers and audiences together to experience ourselves, our distinctive cultural moment, right now, in a new way, and comment on the impact we have as humans—perhaps even including the dissonance between analog and digital—then bring it on!”

At the core, Dorfman believes dance is more than performance—it’s a form of healing. “I love this question,” he says, “as, albeit potentially ‘corny,’ I believe that dance is a healing action. And the following is not just for professional dancers, but for anyone, dancing anytime, anywhere—whether you’re dancing in a rehearsal, or on a stage, or for fun at a park, or in a jam, or at a workshop—or experiencing a performance as an audience member—that unique, kinetic charge that you create in your body and pass on to others is a way to feel totally alive and to bond in real time with other people. And this kind of intimate, non-sexualized physical bonding is so unbelievably essential at this moment in our history. Not only because we have developed an unreal dependence on the immediacy of screens, but also because there is so much divisiveness being spewed about in all media, that we must turn to our bodies as a receptacle of hope, resilience, and embodied intelligence.”

“There are many in our world that don’t have the opportunity to move their bodies freely due to a whole host of factors—so to me, it is even more crucial that we move, in whatever way we can, to counteract overly dominant, repressive actions, oppression, and hatred. Dance is peace building, healing, loving, caring. I often say that if you’re dancing, you’re not hurting another human being. So, and dream with me for a moment—if we could somehow commit to the entire world breaking off into small momentary dance hubs, touching the skin of another person safely, once a day, once a week, once a month, once a year—we would have a more humane universe!”

Now approaching 70, Dorfman says his relationship to his body has changed but deepened. “Thanks for those kind words,” he says, “I’m not sure they are true, but I’ve certainly been around for a while now and have continued to create work and teach all populations and try to build mini-communities of care as I go—and for that I feel extremely thankful and very lucky. Whenever I have a query, intense mystery, or disagreement with my body, I tend to make a dance about that, and my relationship to my body has changed quite a bit over time. Although nearing 70, I feel perhaps more grounded, healthy, and inhabited in my body than I’ve felt in years, about which I’m thrilled. I can’t do all I used to be able to do, but I don’t care about that—I enjoy dancing so much now, and appreciate what I can do, and what I learn from others each and every day, in classes or rehearsals, on stage, or while watching performances.”

He recalls his early years with clarity. “As a beginning dancer, I thought I should train myself in choreography and teaching as I feared I’d never be able to learn how to perform well enough to actually do that as part of my career. Thanks to some incredibly generous early teachers like Martha Myers, my mentor in grad school at Connecticut College (where I now have taught for the last 21 years), and a number of other generous souls, I built a bit of confidence in my ability to perform and proceeded to give a good deal of attention to my movement and presence—and I still do. I adore performing to this day. When performance is working, it can make me feel truly honest, and for me, it is a constant source of wonder and expansiveness.”

Dorfman says that seeing older dancers perform—Daniel Nagrin at 63, Trisha Brown, Baba Chuck Davis, Merce Cunningham, Kei Takei—shaped his philosophy. “Kei’s expression, moment of aliving—her notion of urgency in life and art—has always stayed with me,” he says. “Seeing artists in their 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s allowed me to see aging with dance as the way to live the fullest life possible. So, to continue to dance and perform gives me an opportunity to model that all ages and body types can dance, perform, and express for a very long time—and I think that’s an important message. Dance is for everyone at all times.”

As for what’s next, Dorfman is diving into both reflection and creation. With his partner Lisa Race, he’s on sabbatical from Connecticut College, carving out time for long-delayed projects. “Oh boy—what’s not next?” he laughs. “I want to start writing a book about the cross between making work, teaching, performing, and living a life—I’ve got a one-chapter head start, it’s called Artifice is the Vehicle. I’ve always wanted to do a Moth Radio Hour and/or a TED Talk. I love writing and recording songs in our teeny basement band room. And I’ve just begun rehearsals with the company on a project about democracy in our country, which is very exciting and I feel is very necessary—so I’ll continue to work on that on my own and then meet up with the company and our wonderful composer/musicians a few times to do more movement, text, and music creation.”

Still, Dorfman is leaving space for spontaneity. “All that will keep me busy—oh, and I’d like to have a bit of time with no agenda—hard for me, but not impossible. And I’ll take in a lot of art hopefully—as I like to say, ‘All that I’ve learned, I’ve learned from Art.’ Oh, and a lot of wonderful food too, on a daily basis!”

Photo and writing by Josh Sauceda.